Coming up for Air

Venice Architecture Binnale poster

My head has been buried in the field of a war torn country for the past 4 - 1/2 years. I was an architect working within a developing NGO community in Kabul, Afghanistan. At the beginning, I arrived as an Architect that felt trapped in the life surrounded by a world-wide sea of creative-smart individuals absorbed and defined by a capitalistic“ show us what your made of ” market. After 18 years of education and professional practice and the horrifically unpleasant pursuit of an architectural license, (just so much money to be thrown at the “test” of being - at most - a mediocre standardized architect) I had basically exhausted myself professionally, creatively and emotionally. I just started hating architects, architecture and mostly, myself. I was not interested in buildings or the idea of beautiful spaces just for the sake of contributing what I came to think of as a plastic idea about life consumed by a culture of superficial values. If I had to work for another rich, private, commercial client, I would rather of opened a coffee shop where I thought at the very least I would want to wake up in the morning!…. with good coffee and good people. I didn’t know it at the time, as articulating beyond the immediate was difficult, but I was searching for something beyond the iconic physical result of architecture. My temperament, which has probably driven my family crazy over the years, has always taught me a limitless capacity to explore. Which is just a better way of saying, I was and still am a pain in the ass. So, I started thinking, and decided to leave the architecture for the magazines to find a place where there was nothing but architecture and people wanting to make the first step out of always “just surviving”. The reconstruction of Afghanistan, as I quickly learned, was not the building of buildings but more essentially the building of individual people leading to the building of communities. This was to become the architecture that began to restore my desire to create again. Architecture integral with the triumphs of individuals, communities and civil society towards overcoming their internal and external challenges. If I was able to retain anything from being both Afghan and American, it was to find inspiration in holding the space between individuality and a collective consciousness. I rediscovered something by creating space for connection, bridging, and the pursuit of new thought, fundamental to the empowerment and foundation of a free society.

Images from working in Afghanistan.

I have decided recently to come up for air. The 4 1/2 years pushed me now to try and expand beyond working in Afghanistan and continue exploring. Moving from a place that is far removed from the architects I knew and worked with in New York, I am slowly making my transition back to civilization, leaving a place focused on daily survival and into a place of variety and opportunity. I think it’s the difference in the idea of time. One that is forced to seek a solution to an immediate question every hour, minute, second versus someone who seeks a solution to a question over the course of a month, year, or lifetime.

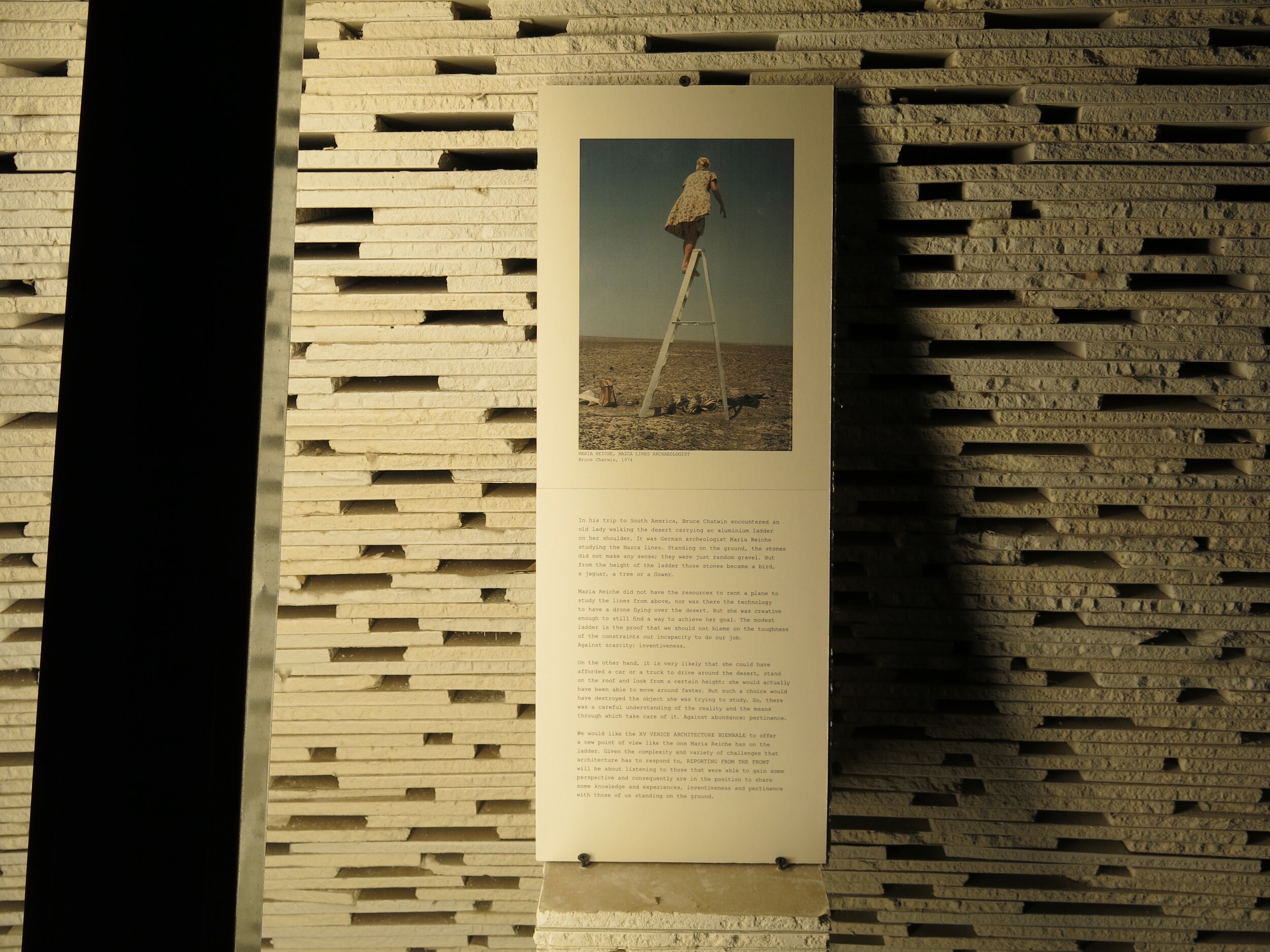

I heard about the Biennale through a friend and colleague whom I worked with in Afghanistan. Then I looked online and saw the image of the German archaeologist Maria Reiche transcending up to nothingness. An image of a person on a ladder to gain a perspective of what appeared like nothing was so powerful to me. I thought I would go if only to see how the interpretation of this image impacted the discussion of architecture. Truthfully, I didn’t have the expectation to go and see good or great architecture. I wanted to observe what the response was going to be to this image. I spent two days during the opening of the Biennale and the people / firms responsible for the projects, were a secondary matter, rather it was more the attitude of what whole architectural shebang. How was this very simple humble image of Maria Reiche standing on the ladder going collide with the world of tycoon-theoretical architecture? What will this industry do with “social impact” once big-private sector is more involved due to the availability of money that will follow after increased public exposure. Will this world become more grotesque and not actually achieve its rudimentary ground-up goals?

For this, i just want to talk about the “Beyond the Front” spaces in Giardini and Arsenale, under the curation of the design director of Alejandro Aravena.

I speak of this work as a total experience by not focusing on any specific architect or project. As Architects, we can get caught up in the issues that are most tangible, the details, the construction the design. One of the questions for an architectural exhibition is how do you represent a building that is existing somewhere else, doing something else, with people somewhere else.

The two curatorial spaces, in Giardini and Arsenale, are very different. Giardini, with its clean white compartmentalized rooms and Arsenale with its long rustic industrial wood trussed space. Alejandro Aravena created an entrance installation for both spaces using recycled material from the previous Art Biennale. The construction of a repurposed gypsum wall, metal studs and light. I wouldn’t say that the installation was thrown together, rather I think that the level of care what just right. The installation was modest, simple, clear and was happy to see it was not concerned with perfection. Yes, you can see screws through the layers of gypsum board from the side if you get really close and the rough edge of the gyp board was left to the celebration of texture. They could have used a table saw to cut the small stackable pieces creating a smooth even surface, but it was rough. It was first and foremost an architectural gesture. It was easy, cut by hand and there were no high voltage machines used. It was not competing for attention; rather it defined an interior space that collaborated with the existing buildings. It felt symbiotic. No need to obsess over the perfection of design, more better to consider the idea of impermanence in a space in which will be disassembled at the end of the year. It was dramatically lit and I think it is a “bravo” to its ability to dare to be an experiential rather than an “overly designed” space of which could be the expectation of an architect looking to satisfy the idea of exceptional design.

As a whole, the exhibits success rested on the notion that we needed to stop looking at projects as a spectator, a model on a podium, a drawing/ sketches on the wall, the completion of a building, rather we engage with the projects in an experiential way, layering many different ideas together. You actually see faces of people that are one to one. You experience humanity, the chaos, the movement, the smell, the struggle, in which gives you an idea of the meaning behind design intent. Design intentions are often not presented with pushing the conditions of human life first, the power of human scale radiating out to meet the architecture. Connecting with many aspects of architecture that are not only focused on the formalism, technology, or materiality of a project. It was not a show for me about solutions, it was an investigation on the human condition in architecture. Yes, there were installations of built completed projects but it was not a full stop. It left room for more ideas and possibility. Projects converge to create a symphony of traditional and contemporary design ranging from small to large budgets, the body and hand on building, the story of survival and community, the strong gesture, the different shades and colors of light projecting through and beyond our human gaze dramatically linking projects, conceptual gaps that leaves one wanting to fill. It is an installation expressing architecture trying to address questions coming from the global socio-ecological planet. It’s why I don’t want to go into specific projects because there we will start to have a different kind of conversation of which is important but for a different time.

Venice Biennale 2016

One thing I have learned about building with a consciousness towards humanity is that architectural practice in a developed context was always, always just a reference point. The model for practicing would always have to continually change and adapt to the context, the people, the education level, the culture, the security situation, the environment… this list could go on. So that this new conceptual architectural practice is guided by the forces of both society and the very important fundamental principles of architecture. You start from the ground and work your way up. You are not hovering over with a formulated architectural theory. Your theories actually could be counterproductive to the project. You must make a discovery in architecture everyday. Yes, every single day, that will be conducive for the people, the place and beyond. You always confront uncertainty in a world of unknowns. It’s when you know your doing something right. It is the essence of this creative work.